The First Monument

The first monument here was apparently a stone rolled by devoted soldiers to the place where Wolfe expired. A benchmark was placed there in 1790 by Major Samuel Holland, the provincial surveyor general. These low-key commemorations answered to the British desire to not yet “honour in such explicit fashion the memory of Wolfe for fear of offending the sensibilities of the people for whom the events of 1759-1760 were still painfully remembered.”

Some of the English deplored what they felt was a lack of respect on the part of their compatriots toward the victorious general. Prior to 1827, the only memorial to Wolfe was a small statue on the corner of Saint-Jean and du Palais streets. An obelisk was subsequently erected in the Governor’s Garden by Governor Lord Dalhousie. Contrary to customary practice, the monument paid tribute to both fallen generals, Wolfe and Montcalm, in an effort to improve relations between French and English Canadians. However, this gesture was not enough to appease the desire among the English to commemorate one whom they felt was a hero of the Empire.

In 1832, Lord Matthew Whitworth Aylmer, the Governor General of British North America, attempted to rectify the problem by replacing the deteriorated marker on the spot where Wolfe died on the Plains with a real monument, a truncated column with the inscription,

Here died Wolfe victorious - September XIII – MDCCLIX.

Wolfe Monument

DirectionsThe height of the nationalist movement

Erected at the height of the nationalist movement, just a few years before the revolt of the Patriotes, the monument acquired tremendous symbolic significance.

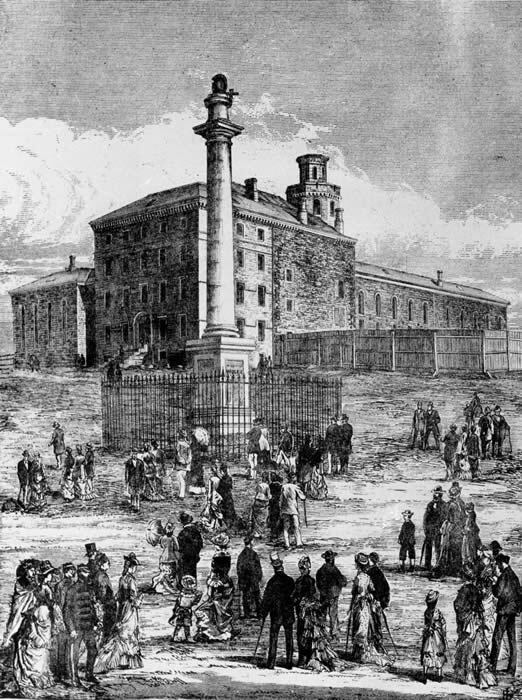

The power of this symbol would eventually be the cause of its premature demise. It was common practice among visitors of the day to take a piece of the column for a souvenir. Such was its deterioration that by 1849 the monument had to go. In its place was erected a Doric column surmounted by a helmet and sword, a gift from the British army posted in Quebec City. The plaque from 1832 was retained and a second one installed along with it. This time, an iron fence with points was built around the monument to protect it from souvenir-hunting visitors. After more than a half-century of weathering, the monument was replaced in 1913. The National Battlefields Commission ordered a granite reproduction of the column, but kept the plaques and head pieces. A third plaque, describing the history of the preceding monuments, was added.

The symbolic value of the site was reaffirmed with the rise of Quebec nationalism in the tumult of the 1960s. For many French-Canadians, the Wolfe Monument was erected to commemorate the defeat of the French Canadian people and stood as

both a symbol of its relegation to the role of a perpetual minority and an affront to its dignity. [translation]

On the night of March 29, 1963, the monument was overturned and destroyed in a gesture ushering in a new extremist group, the Front de libération du Québec (FLQ). On Victoria Day, May 24, 1965, when thousands of rioters were massed in Montreal’s Lafontaine Park, the base of the Wolfe Monument was defaced with paint.

A symbolic importance

The re-erection of the Wolfe Monument, deferred until 1965, involved the National Battlefields Commission in the political and linguistic debate in spite of itself. Prior to 1963, the commemorative plaques on its base were written in English only. They were stolen a few months after the demolition of the monument. When a fifth monument was erected in July 1965, it came with new bilingual plaques, in the same year in which the Royal Commission on Bilingualism and Biculturalism (the Laurendeau-Dunton Commission) submitted its preliminary report. The new plaques omitted the word “Victorious” after “Here Died Wolfe,” “because some groups of citizens were touchy about it.” [translation] The omission raised a controversy in the Anglophone community, where it was felt that Wolfe had been deprived of his victory. The accusation of softness on the part of the government echoed in the precincts of the House of Commons itself.

The controversies surrounding the history of the Wolfe Monument bear witness to its symbolic importance. More than a place of memorial, the monument is a place of both reconciliation and confrontation where, depending on the spirit of the times, the conflict or harmony existing between the heirs of the two armies who fought on the Plains is expressed.